After her recent interview about sensitivity readers in the New York Times, Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, Stacy Whitman, further discusses the role of cultural experts and sensitivity readers and the important part they play in the editorial process.

Over the last several months, outlets like the New York Times have started discussions of the use in publishing of what are now being called sensitivity readers—what we here at Lee and Low have called cultural experts. In particular, the New York Times framed their take on the subject as a question of censorship. The current headline reads, “In an Era of Online Outrage, Do Sensitivity Readers Result in Better Books, or Censorship?” which is updated from the print version, “Sensitivity or Censorship? The Vetting of Children’s Books in an Era of Outrage.”

I’m not sure that the update changes the framing, which still implies that what should be a standard part of the editorial process is somehow a form of censorship.

As the editor and publisher of Tu Books, I have been consulting with sensitivity readers from Day 1, not only for books written by white people, but also for our books that involve intracultural details that may not be known by our authors and for cross-cultural details, as even “Own Voices” books might feature minor characters who are from different cultures than the author.

One of the biggest frustrations I have as an editor is hearing readers say, “Where was the editor?!” for books they have problems with. I think this comes down to a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of an editor—or a sensitivity reader—in the editorial process of the book.

An editor is the author’s first reader in a publishing house.

An editor is the author’s first reader in a publishing house.

They are the first “audience member” outside of family and close friends/writing groups/beta readers for an author. As such, we are the people who can tell the author where the book is working, and where it falters.

Good editors can make a bad book better or a good book great because they can ask good questions. They challenge authors to dig deeper and tell a better story, to refine language, to improve thought processes, etc.

What they cannot do, however, is write the book for the author. I might make a suggestion (“What if this character were to do this instead?” “The pacing is flagging here; consider cutting this paragraph to speed it up.”), but the decision on how to fix the problems I point out ultimately rests with the author.

The editor is no censor of a book, but a partner with the author to put a book out that the author would be proud of.

The same goes for sensitivity readers.

What does a sensitivity reader/cultural expert do? They are experts who can give the author feedback on whether they’re perpetuating stereotypes, fact-checking small details, and in general helping the author make sure that their book is as good as the author can make it.

As with editors, good cultural experts only help when the author takes the reader’s advice.*

What that means in practice is that the book is still the author’s, for good or ill. That is: sensitivity readers are not a ward against getting something wrong. Editors are not a ward against getting something wrong either. So the bottom line is that an author gets feedback from editors and from sensitivity readers and then makes decisions for their book—which remains their book.

And whether they’ve succeeded still remains on the author as well. This is why we hand awards for books that succeed to authors, not to editors. (There aren’t that many awards for editors. We’re actually trained to be as invisible as possible in the public eye, as far as the book goes.)

There may be very, VERY rare occasions when authors and editors have such a vast difference of opinion over what should be done in a book that they break ties over it. But it’s vanishingly rare. The editorial process is one of negotiation, and usually editors and authors figure it out in a cooperative process.

Why do we consult cultural experts?

As children’s and YA author Jason Reynolds so aptly said on The Daily Show last week, we publish books for children because we are “of service to young people.” Everything we publish should be something that edifies, entertains, and/or teaches our readers, that lets them know we see them, and that they are welcome in the books we publish.

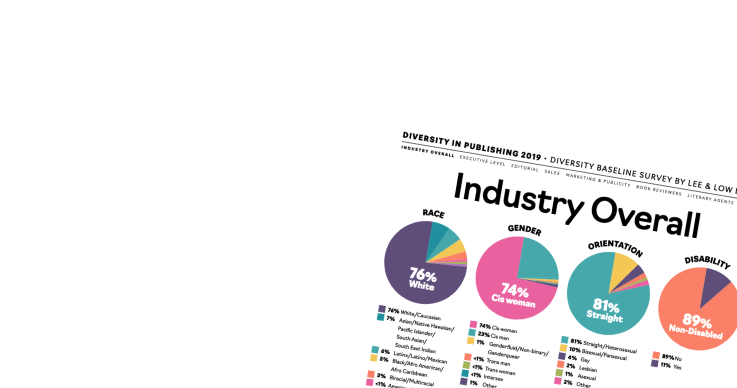

Cultural experts are just one tool in a publishers’ toolbox for equitable publishing—a toolbox that should include publishing a wide variety of authors of color and indigenous authors, diverse hiring practices in all departments, antiracism training to help staff understand and overcome their hidden biases, and more.

*(And it’s also important to remember that there are a lot of experiences within cultures, so sometimes what’s “authentic” to one reader isn’t to another. Just the other day, an author friend with obsessive compulsive disorder mentioned that he didn’t think a YA book he’d just read did a good job of representing the disorder, and it showed that the author of the book didn’t have OCD themselves. When another person pointed out to him that the author did, indeed, have OCD, it became a teaching moment about mental illness for everyone in the conversation: not everyone experiences the same condition the same way.)

Further Reading:

Why We Consult Cultural Experts During the Editorial Process

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse middle grade and young adult titles.

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse middle grade and young adult titles.