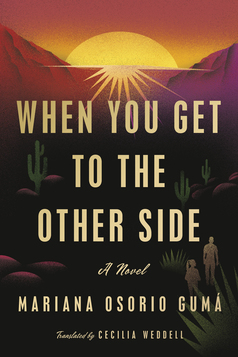

Days before When You Get to the Other Side published, its author, Mariana Osorio Gumá, and translator, Cecilia Weddell, sat down to have a conversation about the book, what inspired it, and the process of its translation. Osorio Gumá joined the video call from her patio in Amatlán de Quetzalcóatl, where she spends most weekends; the enormous leaves of monstera plants decorated the scene behind her as she told Weddell about the decades it took to get the story onto paper and her experience seeing the novel find its way into English. Their conversation, transcribed and translated below, has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Cecilia Weddell (CW): I want to ask you to tell me about Amatlán. Because—well, you’re there now. But how did you end up there for the first time? What is your relationship with Amatlán like, and when did you decide to use it as the setting of a book?

Mariana Osorio Gumá (MOG): Well, Amatlán is a place that I’ve known now for about twenty-eight years. My husband is an architect and he built us a little house here, and we’ve been coming regularly since then. Amatlán is my home now; I’m from here now—it’s one of the places I’ve lived longest in my life.

I adore the atmosphere of this place. It’s a low woodland, but the climate ranges. I mean, when it doesn’t rain, it’s very dry, so there are lots of cacti, agave. But when it’s the rainy season it’s very humid, so there’s moss, ferns. And I think that—especially in the humid rainy season—in some way, for me it evoked (and evokes) my childhood in Havana. That atmosphere that’s a bit, let’s say, tropical.

CW: Where everything is alive.

MOG: Yes. In reality the plant life here is very different, but there’s something about the ambiance. I’ve always liked that. But also, when I came to Amatlán, I started to hear lots of migration stories.

CW: From the people you met there?

MOG: From the people I met here. Many of them are migrants and many of them are contracted to go to the United States for a season to work on tomatoes or cherries or who knows what else. So they go and then they come back, and many of them have had journeys through the desert. Those stories always seemed very interesting and very intense to me, and very striking. I started to write this novel, with them in mind, around twenty-two years ago.

CW: Really?

MOG: Yes—it was the first novel I started to write. It’s not the first I published, obviously. But yes, I started writing it then, by hand, in a notebook. And Emilia was already in the story. Lots of the characters and the settings were already there since then. The story was very different at the start, but lots of it was already there. Between Amatlán, my own migration story, and the stories I heard—well, it all started to mix together.

I left the story alone for many years, but I came back to it after I published Tal vez vuelvan los pájaros. After that book, I took it back up again and worked on it for about two full years.

CW: What was the research process like? Years after hearing all those stories firsthand from people in Amatlán, did you also read about the situation of child migrants?

MOG: Yes, especially in those two years that I was working on the book in a more organized way. I looked through lots of migrant testimonies, from mothers, from families. There aren’t many firsthand stories from child migrants—often it can be so traumatic that many years have to pass . . .

CW: To see it clearly.

MOG: Exactly, and to be able to put words to the experience, right? The majority of the Ventura siblings’ story I made up, imagining what it would be like for two young people like them to migrate. It really troubles me to think about it—I mean, how? How can so many of these children, who are so little, travel alone? And they’re exposed to things that we truly can’t—

CW: Can’t imagine.

MOG: Right. They’re terrible, terrible stories. So between what I read and what I imagined, what I saw on the streets, and what I saw or heard in Amatlán—well, all of that got added to the pot.

CW: Another element is that of curanderismo and the story of Mamá Lochi, the Ventura siblings’ healer grandmother.

MOG: You know what, Mamá Lochi was inspired by a woman who helped me with taking care of my kids while I was working. She’d tell me lots of stories from her town. The parts about lightning in the novel—those came from her. She’d tell me about how she could see the lightning bolts come in through the doors of her house and they’d burn the palm bedmats, for example.

CW: I was just rereading that part of the book!

MOG: Well, she told me about that! And I would tell her: I can’t believe it, how can that be? She wasn’t a curandera, but she was a great mother. She was so, so warm. So I added a bit of my imagination there, too. I read, for example, the story of María Sabina, and histories of Mexican curanderas. And Mexican traditional medicines have always interested me. So while a lot of it comes from my imagination, as a writer you hear little things here and there and suddenly it all starts to effervesce and a story appears that you want to tell, you know?

CW: The threads start to weave themselves together.

MOG: Yes, yes.

CW: Among the things that are weaving together . . . you’re also, professionally, a psychoanalyst. How do you think that influences your writing or your approach to writing?

MOG: I think it influences a lot because psychoanalysis and creative writing have a lot in common, though they’re very different tasks. What I mean is that both work with stories, both work with language, which is my great passion. Of course, it’s not the same thing to work with a story from someone’s life that they’re telling you as it is to work with a story that you’re making up. But because of that work I listen to lots of people, which is like entering into different worlds—hearing someone tell their story is to step into another point of view.

CW: I imagine that having a narrator who is a girl, or a boy—or both, in this book’s case—gives you possibilities of narration that you wouldn’t have with an adult point of view.

MOG: I completely agree. That’s an incredible thing. I think that children see the world in totally surprising ways, which makes them such great characters. It’s fascinating to see how they encounter the world; they’re always creating in their minds and always creating with language, too. It reminds you of the wonder and the surprise in the world, no? Sometimes we lose sight of that.

CW: I think it works really well in this book, too, because Emilia is totally open to learning and marveling at everything her grandmother tells her.

Well, we should discuss the translation process—

MOG: I want to ask you: How did it go for you?

CW: Well, I loved it. I’ve told you this before, but while I was working on translating this novel I was also working on my doctoral dissertation, which involved translating the great Mexican writer Rosario Castellanos, who died in 1974. There were lots of times, while I was doing that, that I wished I could email Rosario and ask her: But why did you write that? Or: What emphasis do you prefer here? So that, first—having a living writer I could pester with my questions—was great.

And then, with this book, I felt that I was always learning. I’m Mexican American and my Spanish is Mexican, but there were still things in this book I’d never heard or read before—the word “titipuchal,” for example, which I’d never heard, and even my mom didn’t know when I asked her. I loved learning words like that and experiencing, as you’ve mentioned, that freedom of expression that these narrators had.

Finally, I loved the collaboration between the two of us because I had the sense that you liked it, that you were enjoying the process.

MOG: Yes. I treasure the emails you sent me. I have them all saved because the questions you’d ask me are so, so interesting to me. You made me reflect on language. I’d use certain phrases and words like—well, I’d use the language that the character was telling me to use. But the reflection of the translation helped me be conscious of how I was using language.

CW: What was it that surprised you most about the process—be it about the writing, or about what English could or couldn’t do with the story?

MOG: Listen, I studied English in middle and high school, but a couple years ago I started to study it much more. I started to read it, to listen to it, to take classes. It’s been really interesting because Spanish becomes clearer to me through English. And English—well, of course, I like it very much. I mean, doesn’t English sound so beautiful?

CW: You think so?

MOG: It’s very beautiful.

CW: Nobody ever says that. Everyone thinks Spanish is so romantic and beautiful-sounding.

MOG: English fascinates me. It seems so difficult—it has so many words and so many similar words, which gives it this amazing richness. It’s exciting for me to see the novel that I wrote moved into another language. I mean, it’s such a strange thing. I can see and even feel the novel in English.

I loved that you made the novel yours—you took it in, you loved it, you took care of its language, no? That moved me. Because, well, that opens the novel up even more.

CW: Yes, I was just thinking about how . . . well, the story of this novel is that Mamá Lochi has entrusted Emilia with telling the story when she gets to the United States. And now this book is arriving to the United States to tell the story.

MOG: It’s incredible.

CW: It feels very apt.

MOG: That’s the magic of Mamá Lochi. She made it get to the other side.

***

When You Get to the Other Side is available now.

Download the Discussion Guide.

Mariana Osorio Gumá is a psychoanalyst and writer. She has published seven books of fiction in Spanish, three of which have been selected by the International Board on Books for Young People for their high quality. In 2014, she was awarded the Premio Literario Lipp La brasserie for her novel Tal vez vuelvan los pájaros. Born in Havana, Cuba, in 1967, she has lived in Mexico since 1973.

Cecilia Weddell is a writer, editor, and translator. She has a Ph.D. in Editorial Studies from Boston University, where she translated the newspaper essays of Rosario Castellanos and earned a graduate certificate in Latin American Studies. Her translations from Spanish have been published in journals including World Literature Today, Latin American Literature Today, and Literary Imagination. An associate editor at Harvard Review, she is from El Paso, TX.