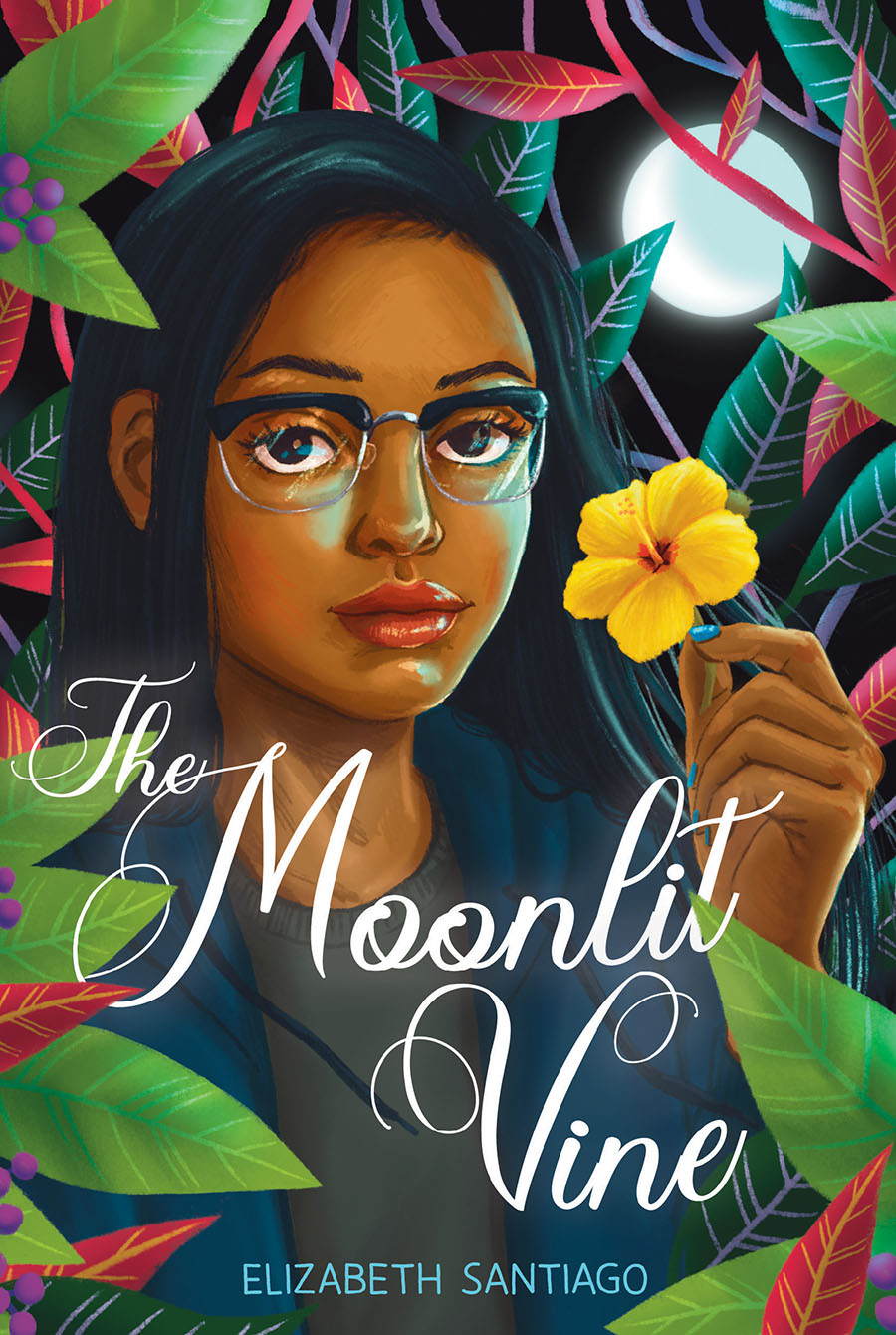

In this guest post, author Elizabeth Santiago reflects on how creating space for storytelling across multiple lived realities and voices creates equity and belonging. The Moonlit Vine & Claro de luna are available wherever books are sold.

⭐ "A beautiful ode to Puerto Rican history. . .. Santiago's writing sparkles, even as it draws upon hard realities that Puerto Ricans can face in their everyday lives and sense of cultural identity. Filled with arresting prose and historical stories, this novel brings Puerto Rican history into the present, mixing in realistic themes to which most readers will relate." —Booklist, starred review

Storytelling and educational equity go hand in hand. Providing spaces for stories to be developed and shared creates an environment where students feel honored and heard, where they feel they belong. Part of creating spaces of belonging include sharing multiple realities and voices. Our stories provide a mechanism for sharing the myriad experiences ever present in our world. No one culture is the same and no one group of people have had the same experiences. In other words, not only do stories matter, but representation also matters. As I think about representation and belonging, I can’t help but reflect on my own writing and teaching journey and the role representation, or lack thereof in some cases, played in my life and career trajectory.

Growing up, I was my mother’s companion. Like many first-generation kids, I became her translator and guide, helping her navigate the world. I went with her everywhere from all her formal appointments to social visits with friends. I was quiet and observant, and what I noticed and appreciated were the stories, especially the ones shared at parties and gatherings. The women my mother surrounded herself with told the funniest and most poignant stories I ever heard. I also observed those same women, when in environments where they didn’t feel welcomed or like they belonged (places like their children’s schools, doctor’s offices, or certain work settings), clam up. Gone were the animated, loving, and warm people I knew in favor of a more suspicious and untrustworthy demeanor.

I personally understood this duality because I struggled to find a bridge from home to school. I was much more comfortable immersed in the culture and environment I knew well. I never found a place for myself in middle and high school. It was as if I wore a costume, and I couldn’t or wouldn’t show my true identity. I felt that no one really saw me or appreciated me for who I was and over time I disengaged. The mask and the foreign ensemble became too cumbersome to wear.

In many ways, I mimicked my own mother who was a powerhouse of a woman, raising nine children by herself in an area of Boston known for crime and violence. When around certain people or in certain situations, she didn’t show her true self. There’s a memory that has stayed with me since my young adulthood. After I dropped out of high school, a social worker asked me why she should help me find a job when I would most likely get pregnant and become a welfare recipient like my mother. It was then I understood that some people had biases against people like us–people who didn’t speak English, who migrated from another place where there were different customs and beliefs, and who were struggling because of poverty. There were limited to low expectations for us.

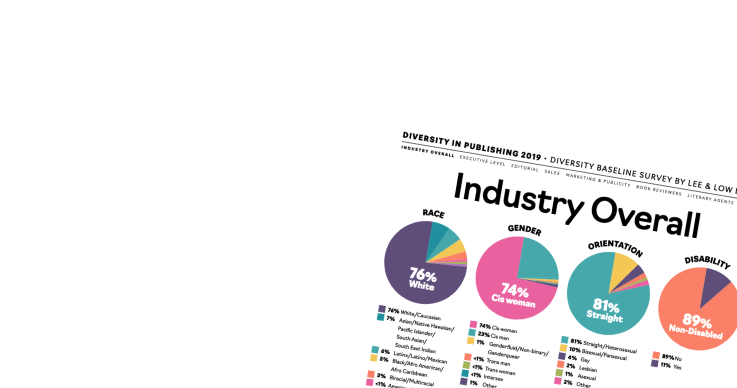

Those low expectations heavily weighed on me even as I did eventually finish high school, earn a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and, most recently, a doctorate. Low expectations were sometimes set by my family because they didn’t know what was possible. More often they were set by others outside of my family or community because of strong narratives about people like me (see previously mentioned social worker). In either case, I entered a lot of spaces alone and without a road map. As I moved up in my career, I saw fewer and fewer people who looked like me or who had similar experiences to mine. There was a lack of representation at all levels, and it caused me to hold back like those beautiful women from my childhood.

I read a lot as a child, but rarely did I read stories about Puerto Ricans growing up in the US or people like those in my family or in my community. I wanted to write stories that represented what I knew and showed us as the complex humans we were. When I started to work outside of my community, I encountered many people who had negative opinions about where I lived. I was confused because while there was occasional violence in my part of the city, there was also love, humor, and genuine caring. I experienced both sides of this coin, but the only narrative out there was the one that highlighted all the deficits. My stories aimed to show nuance and how people in communities like the one I grew up in are there for each other. This lifelong observation shows up in my young adult novel, The Moonlit Vine.

I wrote The Moonlit Vine while in a doctoral program studying the connection between storytelling and adult literacy. I was teaching creative writing to adult high school equivalency diploma students as a way to accelerate their literacy skills. All my students were women, and they all chose to write memoirs. Their bravery inspired me. One student emigrated from the Virgin Islands after a major hurricane. Her home was destroyed, and she told me the only thing she salvaged from the wreckage were two journals. It turns out that she used to write stories herself, but life got in the way of her writing. One morning, she walked into my class with a plastic bag. In that bag were those journals. They were warped from water damage and smelled like something you might pull from a box hidden in the back of an old basement. She proudly showed me those journals and shared the context for what she had written. I felt honored to share that moment with her, and it solidified my belief in the power of storytelling to build community and re-build our humanity.

I felt energized and started a story about the women I had observed my whole life and the women I daydreamed into existence. I thought about the history of Puerto Rico and the ways that colonialism forced my Taíno (the native people of Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, and Jamaica) and African ancestors to hide their voice . . . well from the mainstream anyway. You can hear them loud and clear in the tales they passed down to their children, in the meals they prepared during get togethers, in the rituals they led, in the love they showed, and even in the trauma living like bacteria on their skin. That story became The Moonlit Vine.

The book helped me bring my own voice to the public, to remove the mask and costume. It helped me put to paper, so to speak, my love of history, ancestry, women, and community. And now, I am adding to the representation of Puerto Ricans in literature as well as representations of the Taíno. The main protagonist is a young woman who is finding her power through the women in her family and in her ancestral line.

Representation not only means seeing characters that look or sound like you, but also reading stories in our native languages that represent our expressions and the ways we turn a phrase. It was vital The Moonlit Vine be accessible in Spanish so that even more readers can see themselves reflected in story.

Puerto Ricans are often told we don’t speak proper Spanish, but I disagree. Puerto Rican Spanish is incredible because it melds our complicated history into our vocabulary. Words like chévere (something special or fun), or foods like ñame (mashed yam) and gandules (pigeon peas) are all examples of Puerto Rican expressions with African origins. Same with words like hammock, canoe, and barbecue, which all come from the Taíno language. The Taíno people are part of Caribbean history. We are a part of Puerto Rican past and present. Our history is represented in the words we breathe in and exhale and there is nothing improper about that. My editor, the book’s translator, and I had long discussions about language and the words we would use to translate English into Spanish for Claro de luna. It was important to all of us that we represented the language as authentically as possible, including the specific ways Puerto Ricans might express certain ideas.

So, how can we be more inclusive of communities, families, and individuals in the environments we create and facilitate? I’ve been thinking about this my whole life and have a few thoughts:

- Be honest about our own bias: Having people that look like you is a start, but they also have to understand that you are worthy and believe you belong regardless of your circumstance. Body language and verbal cues often share the real truth. If a person doesn’t think another is worthy, it will show regardless of what is being said. Do the self-work needed to ensure you’re not bringing biases, consciously or unconsciously, into a space.

- Storytelling: Incorporate storytelling into classroom instruction. Not just written words, but pictorial storytelling, comic book or graphic novel creation, video and audio storytelling, poetry and journal writing. I’ve seen the power of providing a way for everyone to communicate, in the method they prefer, and in the language they prefer. It signals to all that their voice matters regardless of how it is expressed.

- Prioritize the expression of ideas: Everyone tells stories. Build on our natural inclinations by providing storytelling opportunities that focus on ideas and not on grammar and punctuation, especially at first. Grammar and punctuation will come, but ideas need space to grow.

When there is lack of representation, many people don’t live up to their full potential. From my observations over the years, living up to one’s full potential is part internal drive and part external opportunities. If you in any way feel like you don’t belong, then how can you achieve? You honestly need an internal drive that’s made of steel. How many of us have that, and frankly, why should we be expected to? It’s not easy to be on an island when you want to succeed and want great things for yourself and your family. That’s why I have made the commitment to teach and support individuals in learning how to tell their stories. It’s one way to create the representation we need and be there for each other as we continue to create spaces of belonging.