Allie Jane Bruce is Children’s Librarian at the Bank Street College of Education. She

Allie Jane Bruce is Children’s Librarian at the Bank Street College of Education. She ![]() began her career as a bookseller at Politics and Prose bookstore in Washington, DC, and earned her library degree from Pratt Institute. She tweets from @alliejanebruce and blogs at Bank Street College.

began her career as a bookseller at Politics and Prose bookstore in Washington, DC, and earned her library degree from Pratt Institute. She tweets from @alliejanebruce and blogs at Bank Street College.

Part 1 | Part 2

Students contemplated book covers

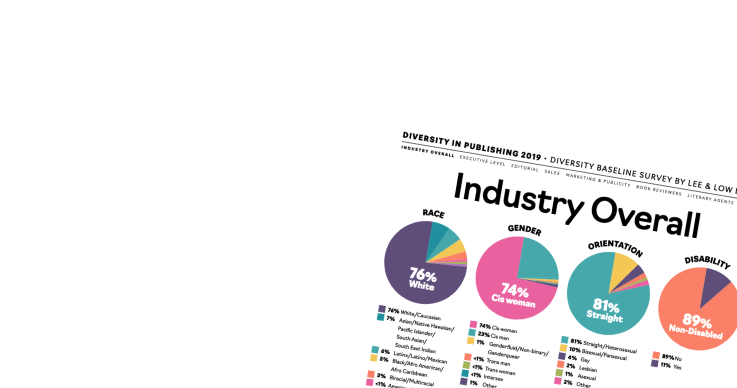

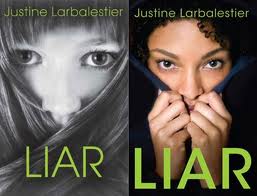

Over the course of the last academic year, I co-taught a year-long unit that allowed a sixth-grade class to explore prejudices in books and the book industry. After studying how book covers and content can marginalize groups (we studied treatments of race, ethnicity, gender, body image, sexuality, class, ability, and more), we took a field trip to Barnes & Noble—by far my favorite piece of the project. The kids exited the store with steam issuing from their ears.

The next night, I read their reflections with joy, wonder, and, I’ll confess, a tear or two in my eye:

- “It was sickening to look at all the stereotypes, the assumptions.”

- “I think I was on the girls’ side of the bookshelf, but even so, that just shows that Barnes & Noble separates their books by gender.”

- “I know that kids’ minds aren’t developed enough to understand these issues, but as they grow up, I hope they realize how serious this issue really is. People have the right to like any color they want and be anything they want to be.”

- “Society is almost afraid of putting a dark-skinned or Asian character on the cover of a book. I feel like these are minor forms of segregation.”

- “I didn’t see a book with a biracial main character . . . it is not fair in any way.”

- “In the chapter book section, I saw that most of the books that had non-Caucasian characters didn’t have that character on the cover.

- “On the covers, I saw thin, pretty girls. I didn’t see any overweight girls or anyone with acne. I think that these covers shape an idea of perfect in a girl’s mind, and make them want to be like that, even though everyone was born perfect.”

My colleagues agreed that viewing Barnes & Noble’s book displays with a critical, well-informed eye was an invaluable experience for the kids. Diversity Director Anshu Wahi says, “[Our librarian] Allie is very diversity-conscious in the [Bank Street] library, so going to Barnes & Noble helped them see that this is a real problem in the wider world. It really opened their eyes.” Humanities teacher Jamie Steinfeld adds, “A lot of them were thinking about how what they saw affects their younger siblings and cousins. It made the whole unit more important to them.”

As their final reflections show, this group of kids no longer needs me, or any grown-up, to filter societal messages and stereotypes for them. They have built their own internal filters, and aren’t afraid to speak up when those filters catch something. This group will be more wary of microaggressions and less apt to place blame on victims for being too sensitive. And, though it’s cliché to say it, they’ve taught me. They’ve shown me that when I see injustices, I can talk to kids about them, rather than trying—and failing—to push everything under the rug. And most of all, they’ve given me the gift of observing, over the course of the year, how they have built themselves into caring, compassionate human beings.

Part 1 | Part 2