![]() Back in June, Laura Reiko Simeon wrote about how race is handled in Swedish picture books. We’re thrilled to host Laura again as she sheds light on how Swedish picture books handle gender and gender-ambiguous characters.

Back in June, Laura Reiko Simeon wrote about how race is handled in Swedish picture books. We’re thrilled to host Laura again as she sheds light on how Swedish picture books handle gender and gender-ambiguous characters.

You sit down with your favorite 4-year-old to read a sweet, wordless picture book featuring a little duck swimming down the river. Quickly, without thinking too hard, what pronoun do you use to describe the duck? Do you say, “Look at him paddle past that shaggy dog!” or “What does she see in the sky?”

If you were like the mothers in a 1985 study, you would use masculine pronouns for 95% of animal characters with no gender-specific characteristics. A follow-up study from 1995 examined children’s use of pronouns and found that by age 7 they had absorbed and were repeating these same gender stereotypes. Listen to those around you: has it changed much since then?

In the US, Sweden is widely regarded as a leader in gender equality, although many Swedes still see a need for greater progress. Meanwhile, our own biases are apparent, for example when we consider gendered toys. Compare this 1981 Lego ad, with its blue jeans and t-shirt-clad girl to the pink-infused products targeted at girls today. As with other social issues, picture books reflect concerns in society at large – but how they’ve done so is dramatically different in the US as compared to Sweden.

Some American picture books encourage acceptance of kids who break free from gender restrictions: Charlotte Zolotow’s William’s Doll, Cheryl Kilodavis’s My Princess Boy, and Campbell Geeslin’s Elena’s Serenade, among others. The point of these stories is that a character is acting in opposition to gender norms, but for children who may not yet be aware that they’re “not supposed to” do or like certain things, these well-intentioned books could introduce self-consciousness.

What have largely been missing from English-language picture books are deliberately gender-ambiguous characters that are neither being bullied nor defiant. They just are. Rather than focusing on the consequences (good or bad) of pushing against societal restrictions or elevating the rebel as cultural hero, they turn the focus on the reader. Do we feel uncomfortable if we don’t know someone’s gender? Why? Do we make assumptions about gender based on what someone is doing or wearing? Why?

We do have some characters – e.g. the diverse, roly-poly infants in Helen Oxenbury’s delightful baby books – that are non-gender specific, but they tend to be in simple, relatively plot-free books for the very young. They are distinct from the Swedish picture books in which pronouns are cleverly avoided and characters send deliberately contradictory gender signals. My earlier post about

Swedish approaches to ethnic diversity introduced the concept of not making difference the problem. There is a similar philosophy at work here.

The Swedish Institute for Children’s Books publishes annual “Book Tastings” that identify trends for the year’s publications. The theme for 2012 was “Borders and Border Crossings,” and one border was gender: not just sexual orientation or gender roles, but the concept of gender as an identifier itself.

The anti-bias publisher OLIKA has published several titles of this nature, but the one that made the biggest splash was Kivi and the Monster Dog by Jesper Lundqvist, the first children’s book to use the gender-neutral pronoun, “hen.” (In Swedish, “hon” means “she” and “han” means “he.” First proposed in the 1960s, “hen” was mostly used in academic research and hipster neighborhoods of Stockholm.) In this funny rhyming story, a small person, Kivi, wishes for a pet dog and ends up instead with a demanding beast that runs amok.

Åsa Mendel-Hartvig and Caroline Röstlund write about Tessla, a preschooler clad in gender-neutral clothes and boasting a mop of brown hair. In Tessla’s Mama Doesn’t Want To! and Tessla’s Papa Doesn’t Want To!, the child, in an amusing role reversal, creatively cajoles badly behaving parents into leaving the park, washing their hair, waking up on time or going to work.

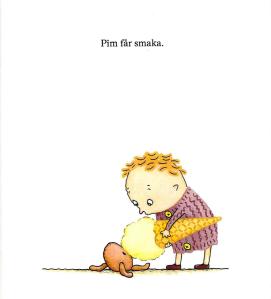

Pom and Pim by Olof and Lena Landström may be the only Swedish gender-neutral book that has been translated into English. The first in a series, it features an adventurous toddler, Pom, who sends mixed gender signals: a boyish-sounding nickname, sparse curls, a long purple sweater, and a little pink toy (Pim). The story is told without pronouns, yet two professional American reviewers assumed Pom was male and referred to the character as “he.”

In Maria Nilsson Thore’s Bus and Frö Each on Their Own Island, two gender-ambiguous animals reach out from their lonely islands to become friends. One is shown variously smoking a pipe and knitting. In Jonatan Brännström’s The Lightning Swallower, we never learn the gender of the narrator, who is terrified of thunderstorms.

These books make a reader consider what markers are “masculine” or “feminine” – and why. They don’t dictate what you “should” do – rebel or conform – or offer value judgments about those who do either. In English-language books, feisty heroines reject traditionally female pursuits as “boring” (what about those girls who do love sewing and cooking?) and boys are persecuted for their love of pink and dolls (making these preferences seem risky to express). With their gender-ambiguous characters, Swedes have tilted the lens slightly and given us a whole new perspective through which to consider this topic. Can we change the terms of the discussion instead of framing everything in terms of binary gender categories? Where could that small but crucial shift take us?

The daughter of an anthropologist, Laura Reiko Simeon’s passion for diversity-related topics stems from her childhood spent living all over the US and the world. She fell in love with Sweden thanks to the Swedish roommate she met in Wales while attending one of the United World Colleges, international high schools dedicated to promoting cross-cultural understanding. Laura has an MA in History from the University of British Columbia, and a Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Washington. She lives near Seattle.

The daughter of an anthropologist, Laura Reiko Simeon’s passion for diversity-related topics stems from her childhood spent living all over the US and the world. She fell in love with Sweden thanks to the Swedish roommate she met in Wales while attending one of the United World Colleges, international high schools dedicated to promoting cross-cultural understanding. Laura has an MA in History from the University of British Columbia, and a Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Washington. She lives near Seattle.