Written by Patricia Garcia-Arena, Ph.D., Principal Researcher at the American Institutes for Research, this blog post explores the need for dual language learners (DLLs) to be exposed to DLL-teaching strategies early on in childhood to promote their learning. Read on to learn how the COLLTS (Cultivating Oral Language and Literacy Talents in Students) program from the American Institutes for Research can do just that.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, more than 11.2 million young children, or 33 percent of all U.S. children under the age of 9, are dual language learners (DLLs).

Language development for DLLs is similar in some ways to the language development for children learning only one language—they tend to reach similar milestones in each language at the same time. However, DLLs also experience some unique aspects of language development that results from the interaction between the two languages. For example, DLLs often engage in codeswitching, in which they use words from both of their languages in the same sentence (e.g., “I like that libro”). Research shows that skills in their first language can in fact help them learn similar skills in their second language, particularly if they have a strong base in their first language.[i],[ii]

DLLs also experience advantages that come from learning two languages. For example, research shows that DLLs have higher executive functioning[iii], [iv] (important cognitive skills that help us learn) and theory of mind[v] (the ability to take the perspective of someone else), which is likely because they have a lot of practice in switching back and forth between their languages.

Given their unique strengths and development associated with learning two languages, DLLs benefit from attending early education settings where educators use intentional, DLL-teaching strategies to promote their learning. The American Institutes for Research developed Cultivating Oral Language and Literacy Talent in Students (COLLTS) program to support DLLs in developing their language and literacy skills.

Addressing the Unique Learning Needs of DLLs

COLLTS is a research-based program designed for preschool-aged children, including dual language learners. COLLTS supports the development of:

- Foundational literacy skills

- Oral language proficiency

- Content knowledge (general, mathematics, and science)

- Conceptual knowledge (knowledge of objects, actions, places, time, parts, features, change, causes, classes/subclasses, sequences, and numbers)

COLLTS can easily be integrated into existing instructional programming. COLLTS lessons take approximately 30 minutes to implement, and they can be broken into two different sessions or a circle time and then center time. The lesson units can be implemented in any order, so educators can align units to classroom themes. COLLTS also can be implemented in a variety of settings, contexts, and program models of early learning and care, with both DLLs and students who speak just one language.

COLLTS was developed by the American Institutes for Research. In this series of blogs, we introduce you to COLLTS, explain the research behind the program, and discuss the provide specific examples of how COLLTS can be used to support all students, including DLLs.

How COLLTS Helps Children Develop Language and Literacy Skills

We at The Center for English Learners at the American Institutes for Research (AIR) designed COLLTS to address what research shows are the best ways to support language development, including interactive shared reading and writing exercises and resources that provide students with multiple ways to learn.

Shared interactive reading involves an educator reading aloud to children, while also using questions and other strategies to model reading, engage children, and support comprehension throughout the session. Prereading activities and discussion can help prepare all students, especially DLLs for reading a new story and addressing open-ended questions with scaffolded responses during reading support comprehension. In interactive shared writing, the educator and students co-construct a written passage, where the students share ideas and the educator writes down the ideas. Then students have the opportunity to write their own passage[1].

Research finds that shared interactive reading sessions with children using non-fiction and fiction books provides a meaningful and motivating context for educators to engage their children in understanding and using new words and language. This is also a natural platform to reinforce emergent reading skills (Beck et al., 2002; Coyne et al, 2004; De Temple & Snow, 2003; Senechal, 2002). Further, research points to the promise of using shared interactive writing with young learners (Hall, 2002; Shin and Crandall, 2018). Because college and career ready standards require students to write narrative, informational, and argumentative texts, those writing types can be focused on in the shared interactive writing opportunities of early childhood and early elementary classrooms.

Here’s an example of a shared reading activity in practice, directly from COLLTS. The lesson begins with a warm-up period, where the educator provides background information about the book and reviews the text through a picture walk of what was read in the prior lesson. During the book reading, the educator uses the questions in the curriculum to support children’s language development, foster comprehension of the text, and develop conceptual knowledge. After reading, the educator reads aloud a question that requires children to summarize or make inferences or predictions related to the text.

To help make lesson planning easy, we’ve organized lessons in the educator’s guide into three columns. The left-hand column displays instructions for educators, the center column displays what educators say to children, and the right-hand column displays anticipated child responses.

We know from the research that children learn new words by interacting with words over multiple time, contexts, and through multiple modalities. Effective features of vocabulary instruction include exposure to words in rich, semantic contexts, such as book-reading; explicit instruction of developmentally appropriate words; and promotion of word consciousness or an awareness of and interest in words (Graves, August, Mancilla-Martinez, 2012).

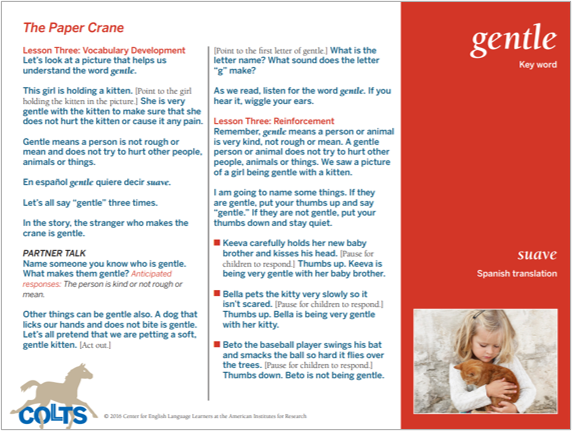

COLLTS also includes double-sided vocabulary cards to teach key words. On side one, each card displays both a picture and the word (in English and Spanish) on one side. Side two shows a picture, a child-friendly definition, a prompt for child to practice repeating the word, reference to the word in the context of the story, and a partner talk activity. Educators can reinforce key words reinforced later during postreading activities using a thumbs up/thumbs down game about the words.

Front of card:

Back of card:

For more information on COLLTS, visit COLLTS: Dual Language PreK Program with Bebop Books.

Dr. Patricia Garcia-Arena is a Principal Researcher at AIR. Dr. García-Arena has more than 15 years of experience in educational research and technical assistance. Her research experiences and interests have included such topics as human development, literacy, cross-cultural child development studies, language socialization, assessment development, and the educational attainment of minority students. As a project director, she has extensive experience managing large federal contracts such as with the Institute of Education Sciences (IES). Along with extensive research experience, Dr. García-Arena has also applied her research knowledge education to technical assistance initiatives to support minority children and their families. She received her Ph.D. in psychological studies in education with an emphasis in child and adolescent development from Stanford University.

Dr. Patricia Garcia-Arena is a Principal Researcher at AIR. Dr. García-Arena has more than 15 years of experience in educational research and technical assistance. Her research experiences and interests have included such topics as human development, literacy, cross-cultural child development studies, language socialization, assessment development, and the educational attainment of minority students. As a project director, she has extensive experience managing large federal contracts such as with the Institute of Education Sciences (IES). Along with extensive research experience, Dr. García-Arena has also applied her research knowledge education to technical assistance initiatives to support minority children and their families. She received her Ph.D. in psychological studies in education with an emphasis in child and adolescent development from Stanford University.

[1] Shared interactive writing combines shared writing and interactive writing. Shared writing is where the educator writes. In interactive writing, the students write, and the educator might provide help to the students. Shared interactive writing, such as the method in COLLTS, combines both approaches—hence it is referred to as shared interactive writing. The shared writing provides a model for the students before the interactive writing.

[i] López, L. M., & Greenfield, D. B. (2004). The cross-language transfer of phonological skills of Hispanic Head Start children. Bilingual Research Journal, 28(1), 1-18.

[ii] Melby‐Lervåg, M., & Lervåg, A. (2011). Cross‐linguistic transfer of oral language, decoding, phonological awareness and reading comprehension: A meta‐analysis of the correlational evidence. Journal of Research in Reading, 34(1), 114-135.

[iii] Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 240-250.

[iv] Barac, R., Bialystok, E., Castro, D. C., & Sanchez, M. (2014). The cognitive development of young dual language learners: A critical review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 699-714.

[v] Goetz, P. J. (2003). The effects of bilingualism on theory of mind development. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 6(1), 1-15.