In this blog post, Katie Potter, Senior Literacy Specialist at Lee & Low Books, offers guidance on curating a social-emotional learning library and reinforces the necessary role that diverse books play in building an SEL collection. This blog post first appeared on the Center Of Responsive Schools’ Two Sides of the Same Coin.

As teachers, we know how difficult it is to explain and define emotions in concrete terms. A situation arises and we grapple with how best to approach it with the students. What are the right words to say that will resonate with them after a disagreement? How do we explain empathy or resolve a student conflict in a way that young people will understand? It can be a challenge to act quickly and make a meaningful impact when there is minimal time to prepare.

This is where books can come into play. By allowing the characters and engaging storyline to do the heavy lifting, books can take the onus off of teachers, presenting to children both the problem and the solution in a safe way that will reverberate with them.

Creating a Social-Emotional Learning Library

Creating a Social-Emotional Learning Library

Books have always been the center of our curriculum: we have a mentor text for teaching historical fiction, a civil rights unit, and a model for valuable decoding skills. Just as we have our go-to books for particular content areas, we should have books set aside for social-emotional learning. A library of social-emotional learning could include books about positive relationships, demonstrating empathy, coping with grief, and any other skills or strategies that are a focus in the classroom. Once social-emotional learning themes are determined, the book selection process can begin.

But in order for our social-emotional learning books to convey meaningful messages, students need to be able to relate to and connect with them on a visceral level. When a child sees themselves in a book—for example, a challenging family situation or a child dealing with a friend moving away—the power of that message can be memorable and life-changing. A recent study focusing on comprehension and African American students showed that culturally relevant texts are integral to learning (Clark, 2017), and we should expect similar results in social-emotional learning settings.

Diversity and Social-Emotional Learning

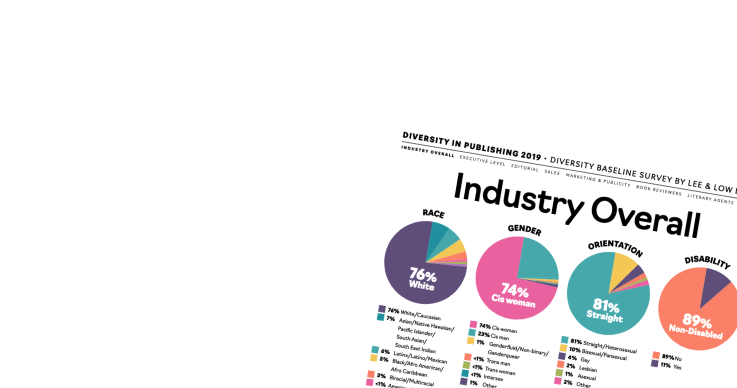

In 2018, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center found that 50 percent of children’s books featured white characters, followed by 27 percent that featured animals (Huyk & Dahlen, 2019). People of color were featured 10 percent or less. What message does this send to our students? This quote from Nancy Larrick’s essay “The All-White World of Children’s Books” (1965) still rings true today:

The impact of all-white books upon 39,000,000 white children is probably even worse. Although his light skin makes him one of the world’s minorities, the white child learns from his books that he is the kingfish. There seems little chance of developing the humility so urgently needed for world cooperation, instead of world conflict, as long as our children are brought up on gentle doses of racism through their books.

Our classroom libraries, and books that exemplify social-emotional learning, should feel intentional and reflective of all students. As we’re building our social-emotional learning library and respective collections, we need to be cognizant of our student body as well as of the world at large. A diverse social-emotional learning library has the ability to generate conversations, build emotional literacy, and provide texts that encompass the skills that students will need for the rest of their lives.

When we reflect our students in our books and are intentional with our text selection, we are not only increasing their own emotional capacities, but we’re also affording them opportunities to better understand one another. Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop uses the vivid analogy of books as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors: mirrors, where children can see themselves; windows, where children can look into an unfamiliar landscape; and sliding glass doors, where children can enter a world different from their own. Says Sims Bishop (1990):

When children cannot see themselves in the books they read, or when the images they see are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in society in which they are a part.

Involving Students in Diverse Social-Emotional Libraries

When teaching social-emotional learning strategies and building a social-emotional learning book collection, student involvement is key. For example, have students go on a scavenger hunt for books that feature a particular social-emotional learning skill and search for titles in their own classroom libraries for characters who demonstrate positive relationships or coping with grief. Here are some recommended titles, by theme:

For perspective-taking: When Aidan Became a Brother by Kyle Lukoff and illustrated by Kaylani Juanita (Lee and Low, 2019), a book about a transgender boy becoming a sibling for the first time.

For kindness: Thank You, Omu! by Oge Mora (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2018), a heartwarming tale of community.

For acceptance: Alma and How She Got Her Name by Juana Martinez (Candlewick, 2018).

For perseverance and strong family values: The Proudest Blue: A Story of Hijab and Family by Ibtihaj Muhammad and

illustrated by Hatem Ali (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2019).

Some additional tools to help diversify your social-emotional library include:

Classroom Library Questionnaire

Guide for Selecting Anti-bias Children’s Books

Diversity and Cultural Literacy Toolkit

Reading Diversity from Teaching Tolerance

We Need Diverse Books

Social and Emotional Learning Diverse Reading List

Avenue A Books

A reflective classroom library and social-emotional learning work in concert: you cannot have a strong social-emotional learning foundation without a library that embodies diversity, and students cannot engage with social-emotional learning without having an understanding of themselves and others.

References

- Clark, F. (2017). Investigating the effects of culturally relevant texts on African American struggling reader’s progress. Teacher College Record, 119(6), 1–30. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1123432

- Huyck, D., & Dahlen, S.P. (2019 June 19). Picture this: Diversity in children’s books 2018 infographic. sarahpark.com blog. Created in consultation with Edith Campbell, Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison. https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/

- Larrick, N. (1965 September 11). The all-white world of children’s books. Saturday Review, 63–65. https://kgrice3.wixsite.com/lcyadiversity/all-white-world-1965

- Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3). https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf

- Page 32 • Self-Care Is an SEL Strategy

- Avildsen, J. (Director). (June 1986). The karate kid part ll [film]. Delphi V. Productions.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020). Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

Katie Potter is the Senior Literacy Specialist at Lee & Low Books. She is responsible for writing and developing the rigorous Teacher’s Guides and Educator Resources for all frontlist titles, in addition to working with university professors and nonprofit organizations on how to incorporate diverse, multicultural literature into curriculum and syllabi. Prior to Lee & Low, Katie worked as an educational researcher, teacher, and literacy instructor. Katie has a dual Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology and Spanish from Skidmore College and a Master’s Degree in Childhood General Education Grades 1-6 and Literacy from Bank Street College of Education.

Katie Potter is the Senior Literacy Specialist at Lee & Low Books. She is responsible for writing and developing the rigorous Teacher’s Guides and Educator Resources for all frontlist titles, in addition to working with university professors and nonprofit organizations on how to incorporate diverse, multicultural literature into curriculum and syllabi. Prior to Lee & Low, Katie worked as an educational researcher, teacher, and literacy instructor. Katie has a dual Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology and Spanish from Skidmore College and a Master’s Degree in Childhood General Education Grades 1-6 and Literacy from Bank Street College of Education.