My final semester as an undergrad was crammed with experiences you might expect of someone full of excitement, optimism, and a lot of what-am-I-going-to-do-with-the-rest-of-my-life thoughts. Aside from the typical pre-graduation nerves, I—as a childhood education major—was about to reach the height of all of the lesson plan and unit plan writing, fieldwork observations, and hours of late-night studying: the student teaching experience.

My final semester as an undergrad was crammed with experiences you might expect of someone full of excitement, optimism, and a lot of what-am-I-going-to-do-with-the-rest-of-my-life thoughts. Aside from the typical pre-graduation nerves, I—as a childhood education major—was about to reach the height of all of the lesson plan and unit plan writing, fieldwork observations, and hours of late-night studying: the student teaching experience.

Seeking a NYS childhood (1-6) and special education (1-6) teaching certification meant that my student teaching placement would be split between the general and special education classroom. This is pretty standard for many education majors, but unlike the public school route, I decided to carry out my student teaching somewhere a little different: at a 12-month, day/residential school for children and adults on the autism spectrum.

Seeking a NYS childhood (1-6) and special education (1-6) teaching certification meant that my student teaching placement would be split between the general and special education classroom. This is pretty standard for many education majors, but unlike the public school route, I decided to carry out my student teaching somewhere a little different: at a 12-month, day/residential school for children and adults on the autism spectrum.

What I knew: I was being placed in a 6:1:6 nonverbal 4th–6th grade classroom, which meant there were six students, one teacher, and one teacher assistant per student. All of my students were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other disorders and disabilities associated with ASD, including ID (intellectual disability), SLD (specific learning disabilities), OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder), and motor and vision impairments to name a few.

What I learned teaching in a special education classroom:

1. Nonverbal doesn’t mean silent. Even though my students relied on the PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System) to tell me what they needed, wanted, and how they felt, our room was the farthest thing from quiet. Instead of spoken words they used their voices and body language to communicate all kinds of information, such as letting me know when they were frustrated, upset, or happy.

I quickly learned each student’s unique sounds, movements, and repetitive behaviors, from various grunts, yelps, and moans to other nonverbal gestures, like finger tapping and hand flapping. It’s important to mention that redirecting students to use the PECS icons was strongly encouraged—a shared IEP (Individual Education Plan) goal—but it was definitely not out of the ordinary to hear a constant deep humming sound, knuckles tapping on the desk, a burst of laughter, a voiced wee sound, the stamping of feet around the room, or see a puzzle piece thrown across the room. This all happened while we taught lessons and led (ABA) applied behavior analysis trials.

No matter how many different special education placements and environments you read about and study, teaching in a room that regularly sounded like indoor recess is not exactly well translated through a textbook. With time I learned to navigate the new sounds and I realized just how important they were to the teachers and the students themselves.

2. There are exceptions to your rules. Aside from specific circumstances, physical contact with students is a very uneasy and thin line to walk for educators. However, the right training and a SCIP-R (Strategies for Crisis Intervention and Prevention -Revised) certification can help you remain balanced and keep your students safe. I learned the appropriate and safe way to use physical prompts, such as hand-over-hand, to help students hold objects, trace letters, and complete many basic tasks.

I also became aware of a range of proactive and reactive strategies, including deflections, arm releases, and more restrictive techniques, to help deescalate challenging behaviors and protect both the student and others. Throwing, hitting, pinching, biting, and spitting were the most challenging behaviors in our classroom, and we often had to deflect students’ throws or hold onto their arms from behind. Seeing a student (safely) restricted from hurting him/herself or others on a mat in the cafeteria or in the hallway was also not an unusual sight, but it certainly took some getting used to.

3. Learning doesn’t stop during lunchtime. To my surprise, the lunch period looked very different from what you might expect in a school. All teachers and teacher assistants ate lunch with their students in the cafeteria. Along with my cooperating classroom teacher and the six teacher assistants, we sat side-by-side with our assigned student at a lunch table. We helped students successfully communicate their food selection using PECS, place food on their tray, eat with utensils, and throw away their garbage, as well as documented their food likes, dislikes, and nutritional intake. In between bites, this usually looked like hand-over-hand prompting to help guide the food from the plate to the students’ mouths while also preventing any grabbing or throwing of food. We can never underestimate a special education teacher’s dedication or ability to strategize.

4. You have more of an influence than you realize. “Kids with autism can’t love or feel love.” Unfortunately, this offensive belief is still out there. Many with ASD struggle with interpreting basic social cues and when combined with other communication and sensory disorders it can make social relationships really difficult. Yet it’s critical to remember that our students are still feeling and experiencing emotions even if they can’t express them in a way we would expect or want.

4. You have more of an influence than you realize. “Kids with autism can’t love or feel love.” Unfortunately, this offensive belief is still out there. Many with ASD struggle with interpreting basic social cues and when combined with other communication and sensory disorders it can make social relationships really difficult. Yet it’s critical to remember that our students are still feeling and experiencing emotions even if they can’t express them in a way we would expect or want.

I still saw and felt my students’ frustration, anger, sadness, happiness, and love far beyond them pointing to the smiling or frowning PECS symbol. For me, the most powerful moments were of my students’ emotional responses to people in their daily lives. It was never predictable, but my students laughed at funny things we did, smiled when we reinforced their successes, and even gave the occasional hug. During the short seven weeks with one of my assigned students, I hoped that he at least liked me as his teacher, and on my last day he patted and hugged my arm. That, for me, said it all.

5. Age-appropriateness is subjective. Respect is not. My students were 4th–6th grade boys, all between the ages of 9-11 years old, but developmentally speaking, they were much, much younger. Most of my students had a favorite stuffed animal and they all cheered and clapped when we played Barney and Sesame Street on movie day. They enjoyed listening to lullabies and ABC songs during the morning meeting, and were learning to identify letters, numbers, colors, their names, months of the year, and other similar preschool-level concepts. It can definitely seem strange that a 9 year old boy is watching Barney, but what are “appropriate interests” for a typically developing third-grader cannot also be said for a child with a developmental disorder.

Respect, on the other hand, is not dependent on development. While I helped these students write the alphabet, wash their hands, use the bathroom, and eat their lunch I treated them with the same dignity and respect that any growing preadolescent deserves. The best way to do this? Know the difference between won’t and can’t and always focus on their strengths, not their limitations.

What has been your experience teaching students on the autism spectrum or with learning disabilities? What resources do you recommend parents and educators explore to learn more? Please share in the comments below.

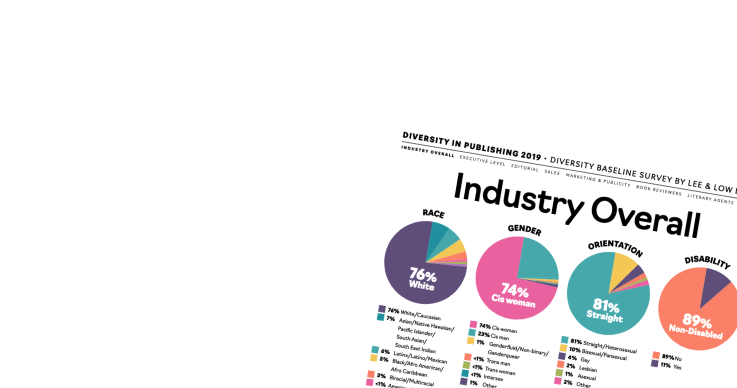

Veronica has a degree from Mount Saint Mary College and joined LEE & LOW in the fall of 2014. She has a background in education and holds a New York State childhood education (1-6) and students with disabilities (1-6) certification. When she’s not wandering around New York City, you can find her hiking with her dog Milo in her hometown in the Hudson Valley, NY.

Veronica has a degree from Mount Saint Mary College and joined LEE & LOW in the fall of 2014. She has a background in education and holds a New York State childhood education (1-6) and students with disabilities (1-6) certification. When she’s not wandering around New York City, you can find her hiking with her dog Milo in her hometown in the Hudson Valley, NY.